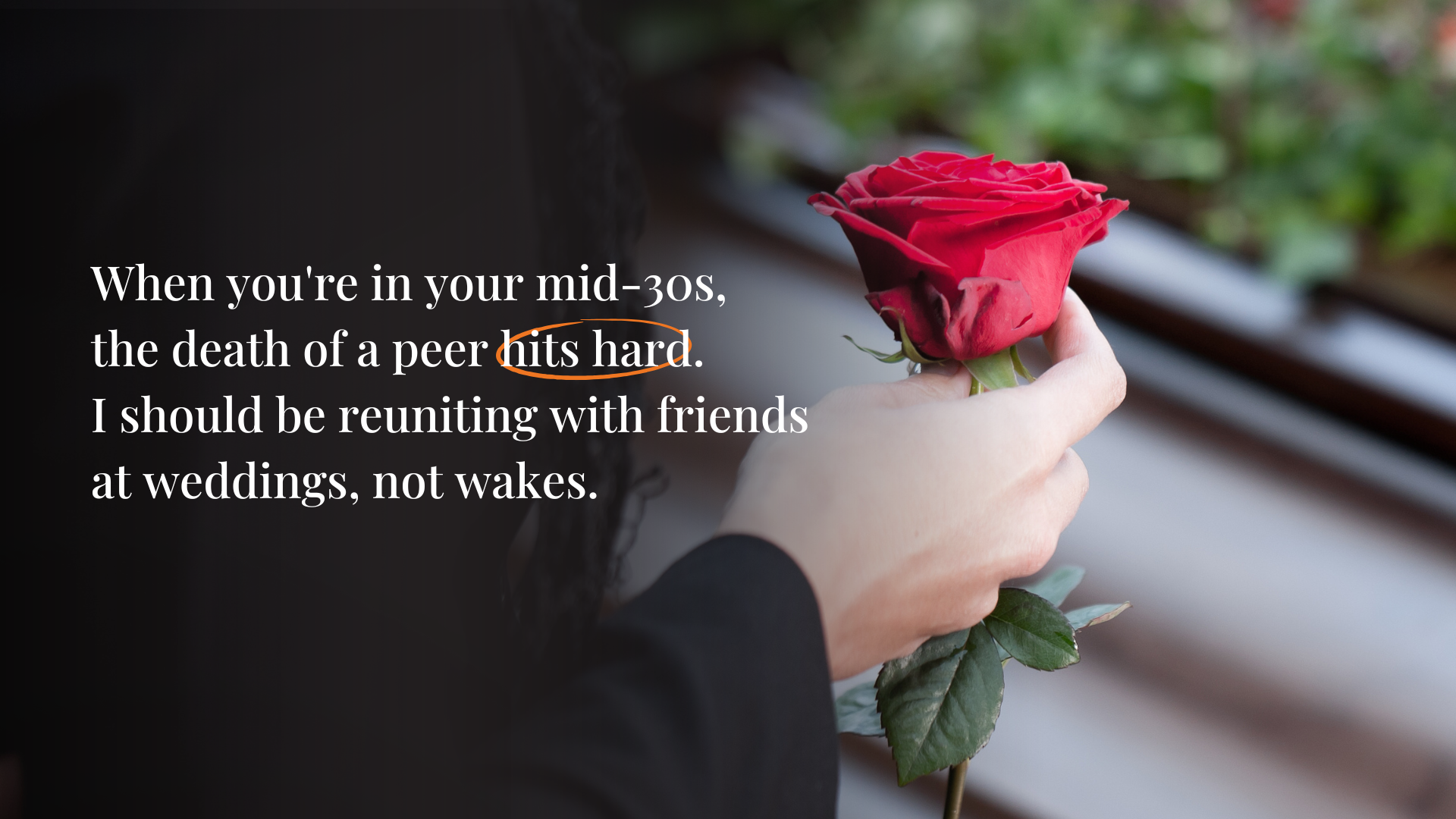

I lost a friend to suicide more than a year ago. I still remember the date: December 3, 2023.

When you’re in your mid-30s, still within the first half of an average person’s lifespan, the death of a peer hits hard. At this age, I should be reuniting with friends at weddings, not wakes. By this time, I already had a few peers who had passed away too soon, due to accidents and unexpected health issues.